In Niger, the encroaching Sahel is a daily constraint for farmers – the wind, sand, dust, soil degradation, water scarcity, and recurring drought make it hard for farmers to provide for their families.

In the northeastern part of Niger, in the Maradi Region, World Vision works with local farmers on Farmer Managed Natural Regeneration (FMNR) to combat the encroaching Sahel. FMNR is part agro-forestry, part environmental conservation, part Disaster Risk Reduction, and part economic driver. It works by finding indigenous tree species, once abundant in Niger but decimated by drought and human population pressure in the 1970s and 80s, and teaching farmers about pruning methodologies to allow those trees to regrow. The regrowth of the trees has shown to reduce surface wind speeds, increase soil fertility, increase ground water availability, increase yields, and reduce surface temperatures.

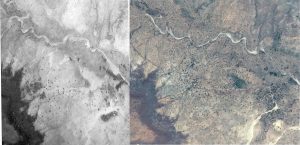

Since the inception of FMNR in the 1980s, its growth throughout the country cannot be understated. Currently, there is roughly 5 million hectares of land re-greened through FMNR, with approximately 200 million indigenous trees. In some of World Vision’s project sites, there is a 250 percent increase in tree/shrub density on FMNR sites and the average tree density increased from 35.57 trees per hectare in 2014 to 123 trees per hectare in 2017. This increase in density is helping farmers increase their staple crop production, primarily millet, by 58 percent due to soil revitalization, increased ground water availability, reduced wind speeds that take top soil away, and reduced surface temperatures in this very arid environment.

Champion Farmer Model

One farmer stands out among the rest – Yaouza Harouna. After incorporating FMNR on his 4.5-hectare rain-fed and 0.5-hectare irrigated land in 2013, he now can fully provide for his family. Yaouza has re-grown roughly 310 new trees, including 60 Sahel apple trees. By implementing FMNR, Yaouza increased the productive capacity of his land and became a sustainable farmer. In the Guidan-Roumdji district where he lives, the average millet yield is 547 kg/hectare,—he produced 937 kg/hectare by planting nearest the bases of his trees. He also produced 450 kgs of peanuts, 250 kgs of cowpeas, 375 kgs of sorghum, 2,000 watermelons, and 833 kgs of Sahel apples from his new trees.

Click here for the full story.

Originally published on the Farming First website.