This is the systematic regeneration of trees from living stumps, roots and seeds. over 5.5 million hectares in Niger, Senegal and Mali have been regenerated this way.

This is the systematic regeneration of trees from living stumps, roots and seeds. over 5.5 million hectares in Niger, Senegal and Mali have been regenerated this way.

This is the systematic regeneration of trees from living stumps, roots and seeds. over 5.5 million hectares in Niger, Senegal and Mali have been regenerated this way.

This is the systematic regeneration of trees from living stumps, roots and seeds. over 5.5 million hectares in Niger, Senegal and Mali have been regenerated this way.

There are two important answers to the question “why do we need more trees in farmland?” One is global and one is local.

There are two important answers to the question “why do we need more trees in farmland?” One is global and one is local.

Globally, trees are often recognized as the ‘lungs of the world’ because they exchange oxygen and carbon dioxide with the atmosphere. However, this is an understatement. If we think in these terms, trees are also the kidneys of the world as they regulate the flow and use of water by intercepting rain and releasing it slowly to the ground where it can either run off into rivers, or enter the groundwater. Plants can then absorb it for use in photosynthesis. This absorbed water is then transpired back to the atmosphere and blown on the wind until it falls as rain somewhere else.

Thus, trees are also like the skin of the world, being the interface between the vegetation and the atmosphere for the exchange of gases and water.

Similarly, trees are like the intestines of the world exchanging nutrients between the soil and the vegetation, fueling the nutrient and carbon cycle.

Finally, they are like the heart of the world, as they drive the ecosystems that make the world healthy and function properly. They do this by providing a very large number of niches for other organisms to inhabit, both above and below ground. Recent evidence has reported 2.3 million organisms on a single tree – mostly microbes – but also numerous insects and even bigger animals like mammals and birds. Others also live in the soil or, due to the microclimates created by the physical stature of the tree, on the associated herbs and bushes. It is all these organisms that provide the ecological services of soil formation and nutrient recycling, feeding off each other and creating an intricate web of food chains.

All this is important for the maintenance of nature’s balance that prevents weed, pest, and disease explosions. They also provide services like pollination, essential for the regeneration of most plants, not to mention the very topical regulation of carbon storage essential for climate control.

Originally published on the Mongabay Website

Every year, the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) brings together scientists from around the world to measure the size of the greenhouse gas (GHG) “emissions gap,” the difference between the emissions level countries have pledged to achieve under international agreements and the level consistent with limiting warming to well below 2 degrees C (3.6 degrees F). That benchmark exists because warming above 1.5-2 degrees C would bring increasingly catastrophic impacts. (Learn more in our post describing the world’s “carbon budget.”)

So what does the Gap Report show for 2017? These five charts explain.

In 2016, global GHG emissions were about 52 gigatonnes (Gt CO2e/year). Total global GHG emissions have roughly doubled since 1970, and have grown dramatically even since 2000. Carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuel combustion, cement and other processes contribute the most, around 70 percent of the total.

Encouragingly, the growth in global emissions in 2015 and 2016 is the slowest since the early 1990s (except years of global economic recession), and global CO2 emissions from fossil fuel use and cement production remained stable in both 2015 and 2016. However, it remains to be seen whether these trends will be permanent.

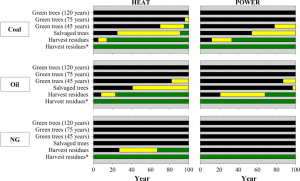

Trees are renewable, so why not let them count under the proposed revisions to the EU renewable energy target? Here we answer this and other questions to demonstrate why burning trees for energy is not inherently climate-friendly.

Trees are renewable, so why not let them count under the proposed revisions to the EU renewable energy target? Here we answer this and other questions to demonstrate why burning trees for energy is not inherently climate-friendly.

The European Union (EU) Renewable Energy Directive establishes an overall policy for advancing the use of energy from renewable sources in the EU. The current framework requires the EU to meet at least 20 percent of its total energy needs with renewables by 2020. Wood is currently the largest contributor to this renewable energy target, accounting for as much as 45 percent of all renewable energy consumed. Much of the forest biomass currently used consists of industrial and harvest residues and traditional fuelwood. However, these sources are nearing full exploitation and further demand for wood for bioenergy will likely come from additional tree harvesting. Even now, Europe is importing wood pellets from U.S. and Canadian forests. Proposals currently under discussion by the European Parliament for a revised Renewable Energy Directive would increase the share of renewable energy in the EU’s total energy mix from 20 percent to at least 27 percent, and possibly 30–35 percent, by 2030. This proposal would likely increase demand to turn trees into energy as EU countries seek ways to meet these more ambitious renewable energy targets.

Originally published on the WRI website.

“I flew from Ethiopia, and you can see it when you fly over the border from Chad to Niger,” says Dr. Kelechi Eleanya, an instructor at the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies. “From the plane window I noticed the colors shift quite rapidly from warm reds to cool greens.”

“I flew from Ethiopia, and you can see it when you fly over the border from Chad to Niger,” says Dr. Kelechi Eleanya, an instructor at the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies. “From the plane window I noticed the colors shift quite rapidly from warm reds to cool greens.”

Though Niger is currently facing slow growth in terms of the human development index, or literacy rate, it is a diamond in the rough for Forest and Landscape Restoration (FLR).

“Niger is an interesting country according to its existing experiences in landscape restoration, and also the dedication by the government on this topic,” adds Horst Freiberg, Co-Head of Forest Conservation and Sustainable Forest Management, Biological Diversity and Climate Change Division at the German Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Building and Nuclear Safety (BMUB).

As a part of the Second Annual AFR100 Partnership meeting in Niamey, Niger, delegates visited local restoration sites: tributary projects that swell together to form a stunning five-million-hectare Nigerien success story in Farmer-Managed Natural Regeneration (FMNR). At these sites, the triumph of this people-centered approach is obvious.

The first site was Tchida village, 55 kilometers West of Niamey. Here, Programme d’Action Communautaire Phase 3 (PAC 3) — funded by the World Bank; Global Environment Facility (GEF), and the Government of Niger — rolled out in 2010 with an ambitious plan to green 120 hectares, primarily using the economically-versatile Gum arabic tree (Acacia senegal).

This sprawling project site was a first encounter with what the local community was calling — in translation — a “demi-lune” method for building up soil carbon and bolstering water infiltration. Also called zaï pits or tassa, this restoration method was detailed in the 2010 documentary film The Man Who Stopped the Desert.

Tchida is situated in a climate of extremes: historically the rainy season has flooded the village and carried away valuable soil carbon and biomass, while the dry season brings a “hunger gap” between the time food stocks run out and the next harvest. Thus a landscape-level solution for restoration on these lands must to address flooding, water infiltration, soil carbon capture and food security.

The answer to all of these woes is deceptively simple: digging shallow pits, filling them with biomass (dung, green compost), planting a nitrogen-fixing acacia in the middle, and surrounding everything with a crescent of sand and rock is enough to stop the floodwaters and force them to percolate down to nourish tree roots long after the rains stop. Whatever they are called in the local parlance, be it zaï, tassa or demi-lune pits, they have the potential to stop the desert.

Originally published on the Global Landscapes Forum website.

Click here for the full story.

“…With the knowledge we are gaining, we will become better land and natural resource managers, because we’re understanding how we need to treat our land, and the plants and animals on it.”

“…With the knowledge we are gaining, we will become better land and natural resource managers, because we’re understanding how we need to treat our land, and the plants and animals on it.”

These are the words of Rinouzeu Karizembi, one of only two women in the nine-member management committee of the Wild Dog Conservancy from the Otjozondjupa Region in eastern Namibia. Rinozeu and her friend Jaqueline Tjaimi are pastoralists who hope one day to make a better living from raising livestock, but, they are also acutely aware of the constraints presented by the arid Kalahari landscape which is their home, the impacts of their livestock, and the effects of a changing climate. With the support their community has received through the GEF-financed, UNDP-supported project on Sustainable Management of Namibia’s Forest Land (NAFOLA), these pioneering young women envision creating a diversified, communally-managed landscape that supports sustainable use of local natural resources for subsistence livelihoods, and provides a safe habitat for plants and wildlife, for the benefit of people and the land.

Rinouzeu and Jaqueline’s story is one of eight included in a new publication, titled “Listening to our Land: Stories of Resilience,”launched by UNDP, Global Environment Facility (GEF), Government of Namibia and the Secretariat for the UN Convention on Combatting Desertification (UNCCD) at the 13th Conference of the Parties to UNCCD being held in Ordos, China from 6 to 16 September, 2017. This publication features a selection of stories that demonstrate how sustainable land management (SLM) addresses land degradation, and promotes the achievement of multiple Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Click here to access the publication

Originally published on the UNCCD Knowledge Hub